Our team has been focusing on the interfacing with both web-based and unity games, and found a growing need to introduce state machines to handle the amount of states we have for entities. Prior to this, we've created a lot of implicit state machines in our services, but it wasn't until we faced a series of consistency errors and impossible states in the database that we figured we should create explicit ones. It was probably more to do with how we read and write to the database within an application session, but it was also a good excuse to look into implementing state machines in our projects.

What are finite-state machines/transducers?

Finite-state machines are an abstract concept that specifies that a machine can only be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. Machines can change from one state to the next through a transition in response to an input from its current state. The canonical finite-state machine doesn't actually have any outputs (as we only classify an input alphabet) and thus can only do read operations; the state transition happens as an internal effect inside the machine. This is where transducers come in.

Finite-state transducers are just finite-state machines with outputs. Inputs and outputs both represent a finite non-empty set of symbols. As such, similar to a transition, an output function may return finite number of outputs.

At Dwarves Foundation, we curate and compose notes with Obsidian Publish. We've written a bit on finite-state machines on our company brainery as an attempt to understand the math behind it:

- brain.d.foundation/Engineering/Reducers

- brain.d.foundation/Engineering/Finite-state..

- brain.d.foundation/Engineering/Finite-state..

- brain.d.foundation/Engineering/Mealy+machine

- brain.d.foundation/Engineering/Moore+machine

Why do we need this?

State machines, by design, don't allow us to be in impossible states or put us in multiple states at once. We can more-or-less guarantee that the state we are in has resulted in how we designed the machine. This is pretty important for data consistency, as well as consistent UI/UX, if you do frontend work.

What is a nested modal transducer?

It's a term Chris Pressey coined as an experimental reactive approach in combining statecharts with purely functional concepts from the Elm architecture:

github.com/cpressey/Nested-Modal-Transducers

In Redux, your application's logic resides in pure functions which have the type

f : State × Action → State

Whereas in the Elm Architecture (or redux-loop) you can write pure functions of the type:

f : State × Action → State × Commands

Where commands represents the countable set of effects that the application can issue. Chris's GitHub entry goes into far more detail about how this is implemented, so I definitely recommend reading it. The few biggest takeaways there were:

- Simple helper function outlines to transition hierarchically nested states and orthogonal states

- Returning effects as symbols to avoid side effects within the machine

Why choose to implement this against other libraries/methods?

Apart from libraries like stateless, there aren't many XState-like packages in Golang for us to choose from. We could have chosen to implement and extend libraries such as redux-loop, but almost all of these methods are pretty overkill, as we don't really need maintain state in the application, we just need to transition it safely.

I also did want to bring light to Chris's writeup on transducers, as it's a great read on its own. The notes, examples, and specifications for nested modal transducers were already 90% of the thought work needed to create a functionally pure statechart-like transducer with no side-effects.

Implementing it in Golang

Before we implement this, we need to make sure what our transition(s) will look like and what it outputs as a function. Transducers usually have 2 functions:

- a transition function such that the next state is dependent on the initial state and its inputs; and

- an output function such that the outputs are dependent on the initial state and its inputs

In Chris's post, to make transducers more ergonomic, the signature for any given transducer is combined as one function:

f : State × Input → State × [Outputs]

Such that our transducer represents a type of Mealy machine that gives us a list of ouputs along with our next state. For our case, we'll treat both of them as one big object to simplify our machine even further. In addition to this, Chris also mentions the use of extended state in a way such that both extended state and finite state become a configuration of the transducer. This ultimately leads into the following signature we'll use for our implementation:

f : Config × Input → {Outputs}

Pseudocode for hierarchical state machines

outerTransducer outerConfig input =

case (outerConfig.mode, input) of

...

(ContainingMode, _) ->

let

innerInput = obtainInnerInputFrom input outerConfig

innerConfig = extractInnerConfigFrom outerConfig

(innerConfig', innerOutputs) = innerTransducer innerConfig innerInput

outerConfig' = embedInnerConfigIn outerConfig innerConfig'

outerOutputs = obtainOuterOutputsFrom innerOutputs outerConfig'

in

(outerConfig', outerOutputs)

...

Our target implementation will be focusing on hierarchical state machines, as it is the more tricky part of statecharts. A lot of the examples in Chris's repository ends up with a bit of boilerplate for merging and transitioning configs and outputs. The good thing is that we can just throw this boilerplate into helper functions.

Approach

Example to work with

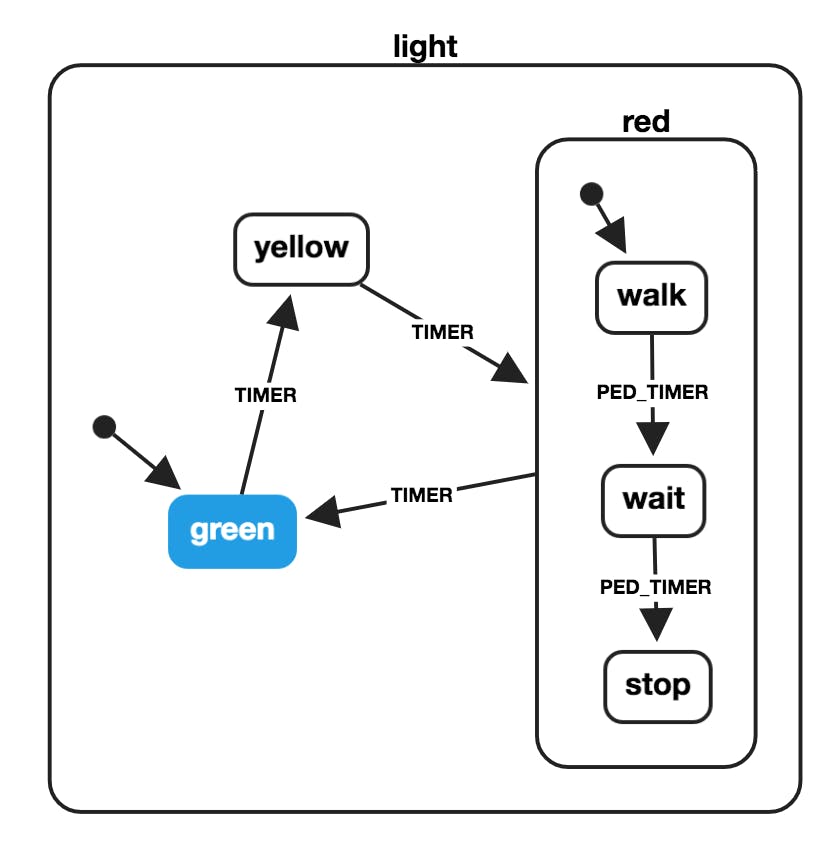

For our example, we will reference the traffic light state machine from the XState docs

The interface

We want our transition table to be ergonomic to create. Apart from nested switch cases or nested mapped structs, the next best thing is to use a simple map that matches with a state and input tuple. This reflects the nested tuples you can do with pattern matching in Haskell:

// transducer/transducer.go

package transducer

// ...

type State string

type Input string

type Effect int

// ...

type TransitionTable map[StateInputTuple]func() *Outputs

type StateInputTuple struct {

State State

Input Input

}

This would allow our transition table to look like so:

// transducer/traffic_light.go

package transducer

// ...

transitionTable := TransitionTable{

{Green, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

},

{Yellow, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

},

{PedestrianRed, PedestrianTimer}: func() *Outputs {

},

{Red, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

},

}

// ...

The state and input tuples (along with the effects we want to output) will be declared in a separate file to organize our constants. This does constrain us to using unique names for each machine, but it's not too bad:

// transducer/consts.go

package transducer

// States

const (

// an invalid state for empty states

Invalid State = "invalid"

Green State = "GREEN"

Yellow State = "YELLOW"

Red State = "RED"

PedestrianRed State = "PEDESTRIAN_RED"

Walk State = "WALK"

Wait State = "WAIT"

Stop State = "STOP"

)

// Inputs

const (

Timer Input = "TIMER"

PedestrianTimer Input = "PED_TIMER"

)

// Effects

const (

UpdateTrafficColor Effect = iota

UpdatePedestrianSymbol

)

// Names

const (

TrafficLightTransducerName = "traffic_light"

PedestrianLightTransducerName = "pedestrian_light"

)

Configs and Outputs

Since our configs and outputs will get a bit hard to compose by hand, we will cheat a bit by taking advantage of the available (but probably non-idiomatic) fluent interface to compose our struct. This makes it easier for other developers to understand and copy the logic:

// transducer/config.go

package transducer

type Config struct {

State State

Data interface{}

Metadata Metadata

}

type Metadata struct {

ChildConfig map[string]*Config

ParallelConfigs []*Config

Test func() error

}

func CreateConfig() *Config {

return &Config{}

}

func (c *Config) GetState() State {

return c.State

}

// ...

func (c *Config) SetState(state State) *Config {

c.State = state

return c

}

// ...

Our outputs here look pretty much the same, but they'll hold our target configuration and a collection of effects:

// transducer/outputs.go

package transducer

type Outputs struct {

Config *Config

Effects []Effect

}

func CreateOutputs() *Outputs {

return &Outputs{Config: &Config{}}

}

func (o *Outputs) GetState() State {

if o.Config != nil {

return o.Config.State

}

return State(Invalid)

}

// ...

func (o *Outputs) SetState(state State) *Outputs {

o.Config.SetState(state)

return o

}

func (o *Outputs) AddEffect(effect Effect) *Outputs {

o.Effects = append(o.Effects, effect)

return o

}

Transition functions and supporting functions

Now for the meat of our transducer, our transition functions. We'll just call it Transduce to go along with the transducer style we're going here. We'll also add support for nested state machines:

// transducer/transducer.go

// ...

// our main transition function

func (t *Transducer) Transduce(config *Config, input Input) *Outputs {

state := config.State

stateInputTuple := StateInputTuple{State: state, Input: input}

transitionTable := t.TransitionTable

f, exists := transitionTable[stateInputTuple]

if !exists {

outputs := Outputs{Config: config}

return &outputs

}

outputs := f()

return outputs

}

// ...

type ChildTransducer map[string]Transducer

// a function to help us merge outputs together

func MergeChildOutputs(outerOutputs *Outputs, innerOutputs *Outputs, childName string) *Outputs {

effects := []Effect{}

effects = append(effects, outerOutputs.Effects...)

effects = append(effects, innerOutputs.Effects...)

if outerOutputs.Config.Metadata.ChildConfig == nil {

outerOutputs.Config.Metadata.ChildConfig = map[string]*Config{}

}

outerOutputs.Config.Metadata.ChildConfig[childName] = innerOutputs.Config

outerOutputs.Effects = effects

return outerOutputs

}

// ...

We'll add some helper methods to help us run transition functions and state related functions for our nested state machines:

// transducer/outputs.go

// ...

// a helper method in our outputs to transition a nested transducer and merge its outputs with the parent's

func (o *Outputs) TransduceChild(transducer Transducer, config *Config, input Input) *Outputs {

if config.Metadata.ChildConfig != nil {

_, exists := config.Metadata.ChildConfig[transducer.Name]

if exists {

innerOutputs := transducer.Transduce(config.Metadata.ChildConfig[transducer.Name], input)

outputs := MergeChildOutputs(o, innerOutputs, transducer.Name)

return outputs

}

}

return o

}

Putting it all together

For our traffic light machine, we'll set it up in a way that accepts a list of possible (named) state machines:

// transducer/traffic_light.go

package transducer

func NewTrafficLightTransducer(setupConfig *Config, childTransducers ...Transducer) *Transducer {

childTransducersMap := MapChildTransducers(childTransducers...)

transitionTable := TransitionTable{

{Green, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(Yellow).

AddEffect(UpdateTrafficColor)

},

{Yellow, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(PedestrianRed).

AddEffect(UpdateTrafficColor)

},

{PedestrianRed, PedestrianTimer}: func() *Outputs {

outputs := CreateOutputs().

SetState(PedestrianRed).

TransduceChild(childTransducersMap[PedestrianLightTransducerName], setupConfig, PedestrianTimer)

childState := outputs.Config.GetChildState(PedestrianLightTransducerName)

switch childState {

case Walk:

case Wait:

case Stop:

outputs.SetState(Red)

}

return outputs

},

{Red, Timer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(Green).

AddEffect(UpdateTrafficColor)

},

}

return &Transducer{

Name: TrafficLightTransducerName,

TransitionTable: transitionTable,

}

}

For our pedestrian light machine:

// transducer/pedestrian_light.go

package transducer

func NewPedestrianLightTransducer(setupConfig *Config) *Transducer {

transitionTable := TransitionTable{

{Stop, PedestrianTimer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(Walk).

AddEffect(UpdatePedestrianSymbol)

},

{Walk, PedestrianTimer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(Wait).

AddEffect(UpdatePedestrianSymbol)

},

{Wait, PedestrianTimer}: func() *Outputs {

return CreateOutputs().

SetState(Stop).

AddEffect(UpdatePedestrianSymbol)

},

}

return &Transducer{

Name: PedestrianLightTransducerName,

TransitionTable: transitionTable,

}

}

As well as a factory function to instantiate both our machines together:

// transducer/pedestrian_light.go

// ...

func NewLightMachine(trafficLightStateStr string, pedestrianLightStateStr string) (*Config, *Transducer) {

pedestrianLightState := State(pedestrianLightStateStr)

pedestrianLightConfig := CreateConfig().SetState(pedestrianLightState)

pedestrianLightTransducer := NewPedestrianLightTransducer(pedestrianLightConfig)

trafficLightState := State(trafficLightStateStr)

config := CreateConfig().

SetState(trafficLightState).

SetChildConfig(pedestrianLightTransducer.Name, pedestrianLightConfig)

trafficLightTransducer := NewTrafficLightTransducer(config, *pedestrianLightTransducer)

return config, trafficLightTransducer

}

Then we can just call our new factory function, transition and log our states, as well as loop and run our effects in an exhaustive way:

package main

// ...

func main() {

config, lightTransducer := t.NewLightMachine("PEDESTRIAN_RED", "STOP")

outputs := lightTransducer.Transduce(config, t.PedestrianTimer)

nextState := outputs.GetState()

nextChildState := outputs.GetChildState(t.PedestrianLightTransducerName)

fmt.Println(nextState.String(), nextChildState.String())

// using our effects:

for _, effect := range outputs.Effects {

switch effect {

case t.UpdatePedestrianSymbol:

// run our side effects here

default:

// error out here to show that we have not exhausted the list of effects

}

}

}

Extras

Generating SQL state machines

This idea came from Felix's post on creating state machines in PostgreSQL: felixge.de/2017/07/27/implementing-state-ma... Since our transition table is just a single map, we can convert it into a nested map to organize and compose our SQL:

// transducer/transducer.go

// ...

func (t *Transducer) ToSQL(initialState State) (string, string) {

stateMap := map[State]map[Input]State{}

transitionQuery := fmt.Sprintf("CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION %v_transition(state text, event text) RETURNS text ", t.Name)

transitionQuery += "LANGUAGE sql AS $$ "

transitionQuery += "SELECT CASE state "

for stateInputTuple, f := range t.TransitionTable {

state := stateInputTuple.State

input := stateInputTuple.Input

outputs := f()

_, exists := stateMap[state]

if !exists {

stateMap[state] = map[Input]State{}

}

stateMap[state][input] = outputs.Config.State

}

for state, inputMap := range stateMap {

transitionQuery += fmt.Sprintf("WHEN '%v' THEN CASE EVENT ", state)

for input, nextState := range inputMap {

transitionQuery += fmt.Sprintf("WHEN '%v' THEN '%v' ", input, nextState)

}

transitionQuery += "ELSE state END "

}

transitionQuery += "END $$;"

aggregateQuery := fmt.Sprintf("CREATE AGGREGATE %v_fsm(text) (", t.Name)

aggregateQuery += fmt.Sprintf("SFUNC = %v_transition, ", t.Name)

aggregateQuery += "STYPE = text, "

aggregateQuery += fmt.Sprintf("INITCOND = '%v');", initialState)

return transitionQuery, aggregateQuery

}

// ...

Our output transition and aggregate queries would look something like this:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION traffic_light_transition(state text, event text) RETURNS text LANGUAGE sql AS $$

SELECT

CASE state

WHEN 'RED' THEN CASE

EVENT

WHEN 'TIMER' THEN 'GREEN'

ELSE state

END

WHEN 'GREEN' THEN CASE

EVENT

WHEN 'TIMER' THEN 'YELLOW'

ELSE state

END

WHEN 'YELLOW' THEN CASE

EVENT

WHEN 'TIMER' THEN 'PEDESTRIAN_RED'

ELSE state

END

WHEN 'PEDESTRIAN_RED' THEN CASE

EVENT

WHEN 'PED_TIMER' THEN 'RED'

ELSE state

END

END

$$;

CREATE AGGREGATE traffic_light_fsm(text) (

SFUNC = traffic_light_transition,

STYPE = text,

INITCOND = 'GREEN'

);

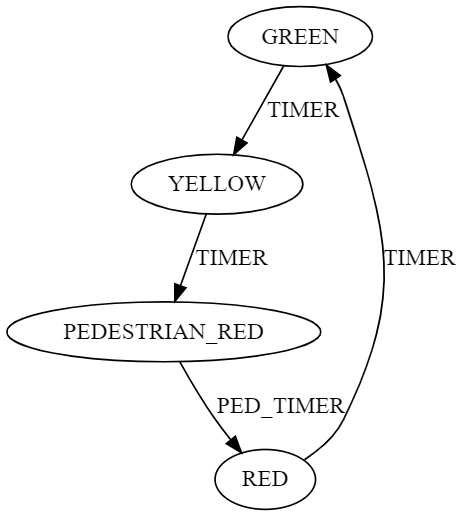

Generating simple DOT graphs (digraph)

We use the same method as above, but we just need to compose a super simple directed graph:

// transducer/transducer.go

// ...

func (t *Transducer) ToDiGraph() string {

stateMap := map[State]map[Input]State{}

digraph := "digraph {\n"

for stateInputTuple, f := range t.TransitionTable {

state := stateInputTuple.State

input := stateInputTuple.Input

outputs := f()

_, exists := stateMap[state]

if !exists {

stateMap[state] = map[Input]State{}

}

stateMap[state][input] = outputs.Config.State

}

for state, inputMap := range stateMap {

for input, nextState := range inputMap {

digraph += "\t" + state.String() + " -> "

label := fmt.Sprintf(`[label="%v"]`, input)

digraph += nextState.String() + label + ";\n"

}

}

digraph += "}"

return digraph

}

// ...

Our output DOT graph state machine would look something like this:

Generating shortest paths

This is totally taken from XState, but its also a good practice in traversing a state machine, which is essentially a graph. Initially, I wanted to implement this with the Dijkstra algorithm, but I couldn't pronounce his name, so I switched to Floyd-Warshall instead:

// transducer/transducer.go

// ...

func (t *Transducer) GetShortestPaths() ([][]graph.Vertex, map[graph.Vertex]map[graph.Vertex]Input) {

vertexes := []graph.Vertex{}

edges := make(map[graph.Vertex]map[graph.Vertex]Input)

edgeWeights := make(map[graph.Vertex]map[graph.Vertex]float64)

weight := 0.0

for stateInputTuple, f := range t.TransitionTable {

state := graph.Vertex(stateInputTuple.State)

input := stateInputTuple.Input

outputs := f()

nextState := graph.Vertex(outputs.GetState())

vertexes = append(vertexes, state)

_, exists := edges[state]

if !exists {

edges[state] = make(map[graph.Vertex]Input)

}

edges[state][nextState] = input

// eh the weights here are added pretty haphazardly; there's probably a better way to do this

_, exists = edgeWeights[state]

if !exists {

edgeWeights[state] = make(map[graph.Vertex]float64)

weight += 1

}

_, exists = edgeWeights[state][nextState]

if !exists {

weight += 1

}

edgeWeights[state][nextState] = weight

}

g := graph.NewGraph(vertexes, edgeWeights)

dist, next := graph.FloydWarshall(g)

paths := [][]graph.Vertex{}

for u, m := range dist {

for v := range m {

if u != v {

nextPaths := graph.GetPaths(u, v, next)

paths = append(paths, nextPaths)

}

}

}

return paths, edges

}

// ...

The graph package we use here is implemented as so:

// transducer/graph/graph.go

package graph

import "math"

type GraphSpec interface {

Vertices() []Vertex

Neighbors(v Vertex) []Vertex

Weight(u, v Vertex) float64

}

type Vertex string

type Graph struct {

vertexes []Vertex

edges map[Vertex]map[Vertex]float64

}

func NewGraph(vertexes []Vertex, edges map[Vertex]map[Vertex]float64) Graph {

return Graph{vertexes, edges}

}

func (g Graph) AddEdge(from Vertex, to Vertex, weight float64) {

if _, ok := g.edges[from]; !ok {

g.edges[from] = make(map[Vertex]float64)

}

g.edges[from][to] = weight

}

func (g Graph) Vertices() []Vertex {

return g.vertexes

}

func (g Graph) Neighbors(v Vertex) (vs []Vertex) {

for k := range g.edges[v] {

vs = append(vs, k)

}

return vs

}

func (g Graph) Weight(u, v Vertex) float64 {

return g.edges[u][v]

}

var Infinity = math.Inf(0)

func FloydWarshall(g Graph) (dist map[Vertex]map[Vertex]float64, next map[Vertex]map[Vertex]*Vertex) {

vertexes := g.Vertices()

dist = make(map[Vertex]map[Vertex]float64)

next = make(map[Vertex]map[Vertex]*Vertex)

for _, u := range vertexes {

dist[u] = make(map[Vertex]float64)

next[u] = make(map[Vertex]*Vertex)

for _, v := range vertexes {

dist[u][v] = Infinity

}

dist[u][u] = 0

for _, v := range g.Neighbors(u) {

v := v

dist[u][v] = g.Weight(u, v)

next[u][v] = &v

}

}

for _, k := range vertexes {

for _, i := range vertexes {

for _, j := range vertexes {

if dist[i][k] < Infinity && dist[k][j] < Infinity {

if dist[i][j] > dist[i][k]+dist[k][j] {

dist[i][j] = dist[i][k] + dist[k][j]

next[i][j] = next[i][k]

}

}

}

}

}

return dist, next

}

func GetPaths(u Vertex, v Vertex, next map[Vertex]map[Vertex]*Vertex) (paths []Vertex) {

if next[u][v] == nil {

return

}

paths = []Vertex{u}

for u != v {

u = *next[u][v]

paths = append(paths, u)

}

return paths

}

func PrintPaths(vv []Vertex) (s string) {

if len(vv) == 0 {

return ""

}

s = string(vv[0])

for _, v := range vv[1:] {

s += " -> " + string(v)

}

return s

}

Our naive shortest paths would output something like this:

'RED' state

RED + TIMER -> GREEN

RED + TIMER -> GREEN

GREEN + TIMER -> YELLOW

RED + TIMER -> GREEN

GREEN + TIMER -> YELLOW

YELLOW + TIMER -> PEDESTRIAN_RED

'GREEN' state

GREEN + TIMER -> YELLOW

GREEN + TIMER -> YELLOW

YELLOW + TIMER -> PEDESTRIAN_RED

'YELLOW' state

YELLOW + TIMER -> PEDESTRIAN_RED

GitHub Repository

The full outputs for all the SQL, digraphs, and shortest paths are available on GitHub. Feel free to fork it if you want to experiment with it:

github.com/monotykamary/nested-modal-transd..

Closing thoughts

I've always found it very enjoying to redo stuff from pseudocode as it gives a bit of insight on what nuances exist for the language you do it on. Of course, this transducer style is being used in production to maintain basic consistency of a game we develop for a client, and it's been working great (excluding the experimental data generation parts).

Having a list of effects is really just a checklist of what side-effects you need to do and exhaust on the list. Switch cases in Golang don't fallthrough by default, which makes it great for this use case. There were a few situations where refactoring logic to use transducers revealed a few actions and effects we were missing in our game logic.

As for the extra stuff, I honestly wanted to try out what I could generate from the state machine. Having clear outputs as clearly defined structs makes this process much easier to work with.

Things to be careful of

We allow for output composition instead of coupling the outputs with the transition table. This means for cases (like the PEDESTRIAN_RED filler state), we can have logic that isn't trivial to generate SQL or dot graphs with without adding special cases for them. For instance, our nested machine must start at PEDESTRIAN_RED and STOP for the traffic light and pedestrian light machines respectively, if we wanted to make sure we can generate the entire machine on the diagram/SQL.

The initial design of the transducer only considered mirrored events/inputs across nested state machines such that it would encourage flat composition of outputs (without using native conditions inside the transition function).

Future work

This article hasn't explored orthogonal state machines yet. It's not too hard to implement helper functions for it, but generating data from it within a single context is not as easy.

In our hierarchical example, we pattern match with a switch case inside our transition function, independent from our outputs. We could make a helper method to help us pattern match through that as a robust way to generate data from nested transitions.